This was a varied year for moviegoing, one that saw plenty of high-profile disappointments (Mad Max: Furiosa is way better than its box office suggests) and surprising successes (who knew a Wicked movie could be good?). But the gems mostly lay in the lower-profile stuff: American indies and international films that spoke to topics both eternally universal and utterly timely. Here are my picks for the best films of 2024—and no, I have not forgotten one major festival hit. If I could have listed the first half of The Brutalist as its own movie, I would have.

© Netflix/Everett Collection.

22. Rebel Ridge

Perhaps one of 2024’s great movie mysteries is why this tense and mesmerizing film from writer-director Jeremy Saulnier was so unceremoniously dumped on Netflix in early September. It eventually found its audience, but how much bigger could the film’s landing have been with a proper release, full of critical ballyhoo? Rebel Ridge is a thrillingly complex and refreshingly humane standoff movie about a somewhat mysterious military veteran, Terry (the terrific Aaron Pierre), teaming up with a local law clerk, Summer (AnnaSophia Robb, also aces), against a corrupt small-town police force. Political concerns of the day certainly come to bear on Saulnier’s wiry, efficient film, but with thoughtful nuance and intriguing moral shading. Saulnier does not shy away from violence, but he doesn’t revel in it either. Here is a new kind of action movie, one about decent characters trying to avoid as much action as they can.

Netflix.

21. Daughters

A moving documentary about a program that unites incarcerated men with their daughters for a dance, Natalie Rae and Angela Patton’s Daughters also concerns the harrowing failings of the justice system. The film is hopeful and devastating at once, and mightily benefits from the virtue of time spent waiting. Rae and Patton followed their subjects for years, allowing the film to encapsulate an epic span. What results is a compelling and wrenching mural of lives interrupted, hanging in stasis even as time swiftly passes.

How to Have SexFrom the Everett Collection.

20. How to Have Sex

A spring-break-esque holiday in Crete, booze-soaked and sun-baked, takes a grave turn in Molly Manning Walker’s striking debut feature. As a young woman who experiences a dire violation of consent, Mia McKenna-Bruce is a revelation, intricately mapping her character’s struggle to process, and name, what’s happened to her. Manning Walker stages a party gone to ruin with bracing realism, resisting sensationalism by leading with compassion instead of alarmism. True to its title, How to Have Sex is instructive in at least one crucial way: It yanks certain predatory behavior into the light, refusing to let it hide in supposed gray areas.

Housekeeping for Beginners© Focus Features/Everett Collection.

19. Housekeeping for Beginners

Macedonian Australian filmmaker Goran Stolevski’s third feature is a rambling, sometimes pummeling found-family drama about a home shared by an interconnected crew of misfits in Skopje, North Macedonia’s capital city. The great Anamaria Marinca plays a health care worker who finds herself taking on the role of den mother following a tragedy, working to formalize some of the bonds holding her motley clan together. Among other things, Housekeeping for Beginners is a sober look at the realities of Roma life in the Balkans, especially for those contending with the additional stigma of being queer in a bigoted society. Stolevski—one of the most exciting emerging directors on the world scene—manages a controlled chaos, keeping his film loose and lively while driving toward a stirring finish.

Courtesy of Prime

18. The Idea of You

An Anne Hathaway movie about a middle-aged woman falling in love with a 20-something boy bander was probably always going to be a good time. But The Idea of You (based on a popular novel) turns a fun premise into something much more. Disarmingly wistful and lushly photographed, Michael Showalter’s film was a lovely springtime surprise. Hathaway is poised, confident, and decidedly grown up as a Los Angeles gallerist who falls hard, if a little reluctantly, for Nicholas Galitzine’s pop idol with a heart of gold. They’re a winning pair, selling a ridiculous fantasy so successfully that it stops seeming ridiculous at all.

17. Red Island

The masterful French director Robin Campillo yet again mines some of his own experience for this evocative picture of French colonialism in 1970s Madagascar. Largely through the eyes of a young boy, we see the fraught social dynamics of a French military base and the locals in its orbit, divides between race and class revealing themselves in troubling ways. But Campillo uses a light touch; his film floats along as if born on the breeze of memory, lilting through vignettes that murmur with hidden meaning. A marriage falters, a forbidden romance feels the terrible strain of social pressure, a revolution foments among the occupied. And in the film’s beguiling closing moments, Campillo gracefully reveals whose story this has been all along.

David Lee/Netflix

16. The Piano Lesson

A sturdy, evocative adaptation of August Wilson’s Pulitzer-winning play, The Piano Lesson gives lie to the idea that nepotism is always bad. Denzel Washington produced this film, directed by his son Malcolm and starring another son, John David. Much of the cast was transposed from a recent Broadway production, which might mean that the work was half done. But Malcolm Washington adds real cinematic heft to the material, creating a dense visual and aural texture to surround captivating performances from John David Washington, Danielle Deadwyler, Ray Fisher, Corey Hawkins, Michael Potts, and Samuel L. Jackson.

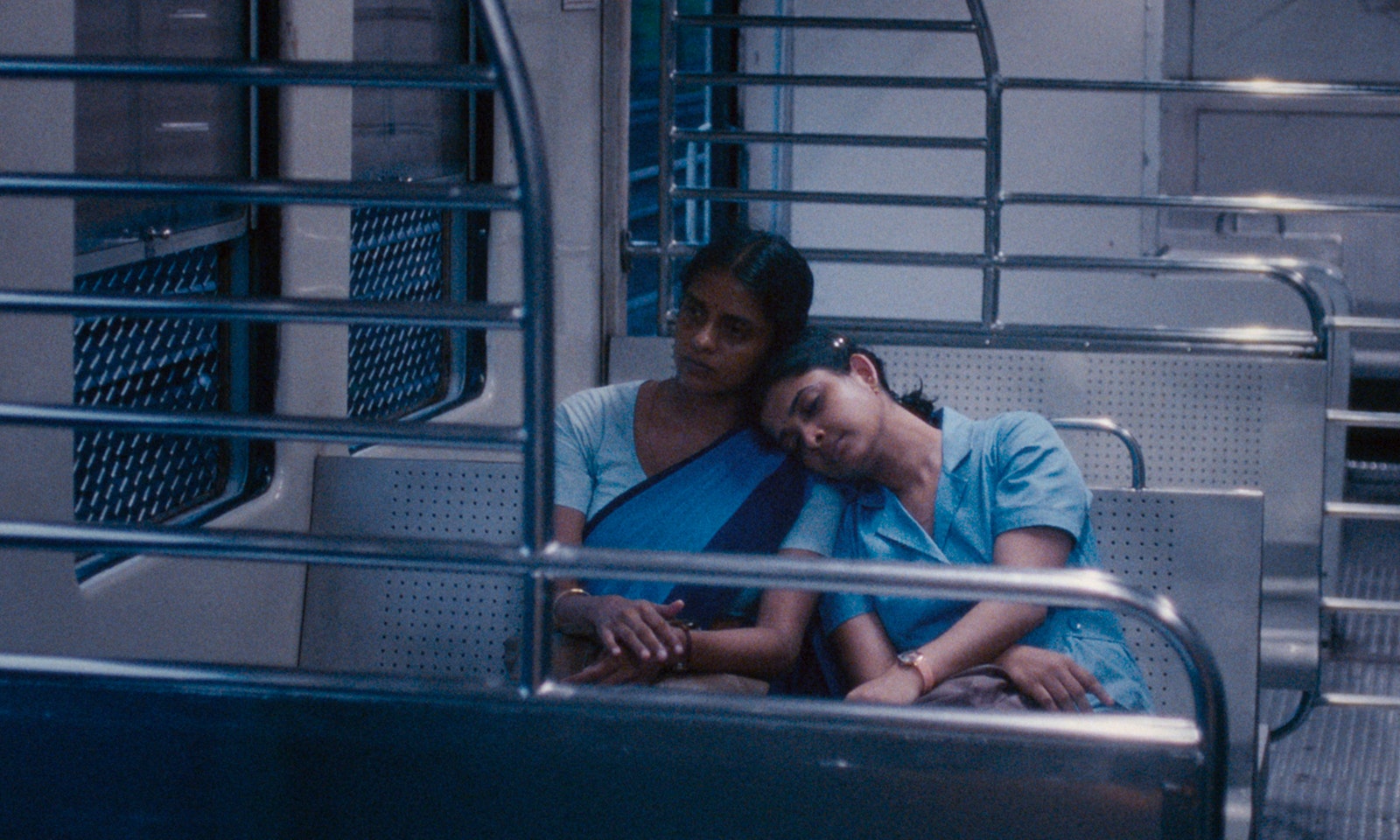

Janus Films

15. All We Imagine as Light

A dreamy, limpid watercolor of three women (Kani Kusruti, Divya Prabha, Chhaya Kadam) living in contemporary Mumbai, Payal Kapadia’s gorgeous chamber piece is a different kind of Indian cinema. It has been criticized by some as too Western, eschewing the favored, long developed aesthetics of Bollywood and Nollywood movies. But in that transgression, if it is indeed a transgression, Kapadia finds a new language to talk about life in a massive and impossibly varied country. Soft to the touch and whispering with quiet poetry, All We Imagine as Light allows for peaceful rumination among the din of a nation in busy flux. Its closing scene feels like a deliverance: Under a vault of stars, there is peace, contentedness, and an unspooling metaphysical wish for the future.

The End We Start From© Republic Pictures

14. The End We Start From

Killing Eve breakout Jodie Comer (who recently won a Tony for her staggering solo performance in Prima Facie) further proves her talent in this somber but never lugubrious survival drama from Mahalia Belo. As floodwaters overtake London, a new mother must head north in search of safety and sustainability while a nation credibly collapses around her. Finely observed and avoidant of melodrama, The End We Start From is a thoughtful, occasionally profound manifestation of a collective anxiety, the shared feeling that the fabric of the world is rapidly fraying to a breaking point. Belo steers through all that fear and calamity and finds something like hope on the other side.

dFlights.

13. Green Border

Venerable Polish director Agnieszka Holland’s furious, heartsick look at the refugee crisis at the Poland-Belarus border is grim but galvanizing. We watch in horror and alarm as people fleeing war and poverty are used as pawns in a brutal political fight, left to wander swampy forests in search of care and compassion. They find it on occasion, as Holland turns her focus to the principled activists who risk their own freedom and safety to help their fellow humans. Green Border won a prize at last year’s Venice Film Festival and was then roundly decried by members of Poland’s conservative government. The film is its own act of daring in that way, a polemic and a cri de coeur that damns its targets and shakes viewers out of complicit inaction.

Ralph Fiennes stars as Cardinal Lawrence in Conclave.Courtesy of Focus Features. © 2024 All Rights Reserved.

12. Conclave

What fun! An airport-novel thriller about the succession of the pope becomes a bit more high-brow than required in director Edward Berger’s confident hands. Berger’s last film was the Oscar-bedecked, technically impressive, but emotionally deadened war epic All Quiet on the Western Front. It’s a happy surprise, then, that he would shed all that grave self-seriousness for a just-shy-of-campy follow-up feature. Ralph Fiennes, Stanley Tucci, John Lithgow, and other talented old men make engrossing high drama out of the Catholic church’s contemporary conflict, convincing us of its importance while also making little winks toward the absurdity of the institution. Plus there’s Isabella Rossellini, who makes the most of her few moments as the lone woman in these stifling rooms saying, “What the hell are all you idiot men doing?” Gourmet popcorn of the highest order, Conclave is the most unexpected mass-market crowd-pleaser we’ve had in quite some time. May there be a hundred more movies like this in the coming years.

Emilia Pérez. Zoe Saldaña as Rita Moro Castro in Emilia Pérez. Cr. PAGE 114 – WHY NOT PRODUCTIONS – PATHÉ FILMS – FRANCE 2 CINÉMA © 2024.Courtesy of PAGE 114 – WHY NOT P

11. Emilia Pérez

Jacques Audiard goes audacious in this wild, rapturous musical melodrama about a trans former drug kingpin (Karla Sofía Gascón) and her noble, conflicted fixer, Rita (Zoe Saldaña), as they try to atone for the myriad violent sins of the past. Not everything lands in the 72-year-old French auteur’s perhaps biggest swing yet—a song about the technical details about gender confirmation surgery too giddily skirts the line of offense—but the aggregate result is something weird, beautiful, and viscerally moving. And what a joy it is to see these actors—four of whom shared the best-actress prize at Cannes, including Selena Gomez—reach for and rise to the movie’s grandeur. It’s particularly exciting to see Saldaña travel far afield of her sci-fi franchise success to wail and thrash her actorly heart out. Vivid and ornate and wholly sincere, Emilia Pérez is singular, a huge spike in the heartbeat-monitor line of the year in movies.

Felix Dickinson/Courtesy Neon

10. The End

Joshua Oppenheimer—who made the searing documentaries The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence—makes a strange feature debut. The End is long, often boring, stilted, silly, and on-the-nose. And yet I just can’t stop thinking about it. It’s a musical about the end of the world, about one rich family trying to thrive and keep the flame of culture alive in a bunker in the depths of a salt mine. There is something pathetic about it, and also immeasurably sad. The songs, offbeat but sometimes soaring pieces by Joshua Schmidt and Marius de Vries, prove to be wholly necessary binding to all this disparate, heady noodling about humanity’s last stand. Tilda Swinton and Michael Shannon make for entirely credible snobs in the final chapter of their epoch, but it’s George MacKay—as a boy raised in the underground—and Moses Ingram—as a girl intruding from the world above—who make the most impact. Their wary and helpless flirtation is a stirring evocation of what so many real-world young people now face: to consider a personal future at a time when the entire planet’s seems so uncertain. The End, so gorgeously staged, is ponderous and difficult and unforgettable.